In 1979, at the age of 18, Alfred Walker stepped into a museum for perhaps the second time in his life, to accept a job that would ultimately shape his future. Having recently graduated from high school, he was still a kid. The museum was a foreign space, and art was a subject, a career path, he had never considered.

Earlier this year, Walker retired from his 43-year career at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth. His name likely isn’t familiar to museumgoers or even the most tuned-in of arts patrons, because, as Head of Facilities, he often worked behind the scenes. But his dedication to his craft, the longevity of his time with the institution, and the scope of work he oversaw made him a valued employee and landed him among the museum’s ten highest-paid workers, according to the Carter’s 2020 tax forms.

Walker graduated from Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in the predominantly Black, Stop Six neighborhood of Fort Worth in 1979. He worked a few odd jobs that summer, but in the fall was still searching for his next step. At the time, his father, Reverend Lee Edward Walker, was working for Bryne Construction Services, which was completing work related to the Carter’s 1977 renovation project. Walker learned about an open position in housekeeping through a friend of his father who worked at the museum. He accepted the position, not knowing what to expect.

Since the Carter was a smaller institution at the time, the housekeeping department was also in charge of art handling and lighting. As the youngest person in the department, Walker found that climbing up and down the ladder to adjust exhibitions’ lighting often fell to him. Right away, he felt a sense of excitement when lighting the artworks — he quickly understood that with the proper lighting, a work of art can come to life in a new way.

With the right direction and mentorship, a young person can strike a new path and make a life for themselves they might not have imagined otherwise. Such was the case with Walker. Though, admittedly, he was not prepared for the shock of working in a predominantly white environment, Walker thrived because he had mentors who had high expectations of him and helped him find his way.

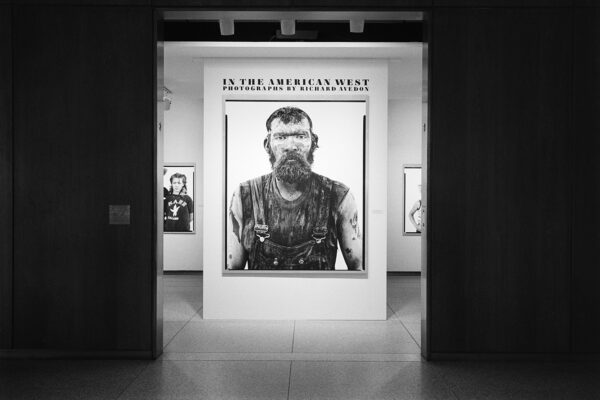

As other staff members saw Walker’s enthusiasm for his work, they helped guide him to learning opportunities. From 1983 to 1985, he volunteered with Hip Pocket Theater, a Fort Worth-based outdoor theatrical venue, to learn more about the art of lighting. At the museum, one of his first great lighting challenges came in 1985 with a major exhibition of Richard Avedon’s In the American West, which featured large-scale black and white portraits of everyday people set against stark white backgrounds. The photographs were commissioned by the Carter from 1979 to 1985, and for the exhibition were hung in the small galleries that made up the original 1961 building.

Walker explains that because the height of the ceiling was so low, the works — many measuring approximately five feet tall by four feet wide — were difficult to light. With little distance between the lighting tracks and the top of the pieces, lighting options were limited. Additionally, the amount of white space in the images created more glare than Walker had been accustomed to. For assistance with the project, Walker worked with Arthur Gressman, a local lighting expert, but Carol Clark and Ron Tyler, curators at the museum at the time, saw Walker’s passion for lighting and realized he would benefit from professional training. They advocated for him to take part in a 4-day training program at the Smithsonian Institute’s Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C.

The training left a lasting impression on Walker. Not only was it his first time on an airplane, but it also cued him into the breadth and seriousness around the profession of lighting museums. Beyond basic lighting training, it was the first time he learned about preservation and how proper lighting can either contribute to or hinder an artwork’s longevity. He also used it as an opportunity to meet with managers at the Smithsonian and gain a broader understanding of the museum world in general. Importantly, the program marked the first time Walker met an African American man working in a managerial position at a museum, inspiring him to see more possibilities for his own future.

At this point in his career, Walker had held a few different positions at the Carter. Later, in 1985, the museum’s chief engineer, Earl B. “Boone” Blakeley Sr., advocated for Walker to move into the engineering department, which would put him on the path for a supervisory position, overseeing housekeeping and building maintenance. Blakeley was a longtime employee and family friend of the Carters. Prior to joining the museum, he worked for Amon G. Carter at the Fort Worth Star Telegram from 1941 to 1977. Walker told me, “Blakeley saw some things in me that I didn’t see in myself, and he helped bring those things out.”

Similarly, Ruth Carter Stevenson, Amon Carter’s daughter, who led the founding of the museum, also served as a mentor for Walker. Though she was tough, Walker recalled that her high expectations pushed him to do his best. Walker has said that she was like a grandmother to him.

As Walker climbed the professional ladder and the museum began to bring in preparators to handle its collection, his museum career veered away from lighting. But, ever-passionate about the work, Walker installed a lighting track in his home garage so he could continue to hone his craft. He would bring in family photographs or framed prints and play with the distance and positioning of the lights. Walker explained, “Even though my job changed, my position changed, it seemed like I was just always drawn back to lighting.”

Around this time, he started offering his lighting services to local people and organizations for free, and soon realized he could turn his passion into a business. In the mid-1980s, with the help of his wife Tina, Walker established his company, Lighting By Design. Over the last three decades he has worked with countless North Texas museums, including the Sixth Floor Museum, the Nasher Sculpture Center, the Crow Museum of Asian Art, and The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. He has also been hired to light private collections in homes as far away as New Jersey and as near as Dallas, including the Green family’s private collection.

Walker has been lighting works in the Green family’s home for about six years. While he enjoys the challenge of lighting homes, which were not designed to function as gallery spaces, he was also excited to have the opportunity to design the lighting for the new Green Family Art Foundation (GFAF) gallery space in downtown Dallas.

Walker told me, “The beauty of lighting design is that every building is unique… every gallery is unique. So, if I have a fix for this one, it may not work in that one. I have to recreate every project. It’s new every time. But, it makes it a lot easier when it’s my design. At the Green Foundation gallery, I know the tracks are in the right position and I can light every wall in that place. My job as a designer, it’s almost like a doctor writing a prescription. I have to write you the right prescription, or right specification, to get the right light.”

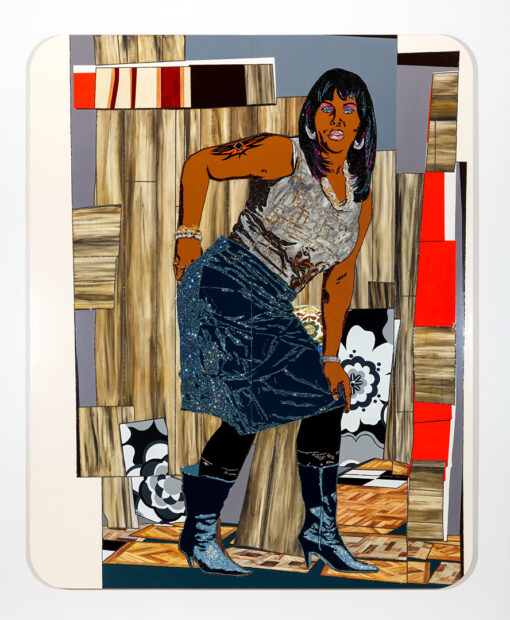

Installation image of a work by Mickalene Thomas prior to lighting. Photo courtesy of Green Family Art Foundation.

Bailey Summers, director of the GFAF, spoke to Walker’s expertise: “Each piece is its own challenge, because no two artworks are the same. Alfred doesn’t just come in and pop lights in, he sits and works with the piece and figures out how it needs to be lit based on the specific needs of the work. He adjusts angles and manipulates the light with various lenses and filters.”

Similarly, Chief Curator at the Nasher, Jed Morse, noted that Walker has been lighting exhibits for the museum since soon after its opening, twenty years ago. While Walker didn’t design the lighting for the Nasher, a local art handling company recommended him, and from his first job with the museum it was clear he brought a wealth of knowledge and an unprecedented dedication to the work. Because the design of the building floods the gallery spaces with natural light during the day, Walker and Morse work on lighting Nasher exhibitions in the evenings. Walker recalled staying past midnight some evenings to make sure the exhibitions had the best possible lighting.

Morse also spoke about how Walker has been encouraging him to switch from halogen bulbs to LEDs for years; just recently, they began to make that shift. Walker has been interested in LED technology because unlike halogens, which send heat in the same direction of the light they emit, LEDs send heat back and don’t emit ultraviolet light, which can damage artwork.

In April, when Walker decided to retire, it was bittersweet. His father never had the opportunity to retire, and Walker had always planned to give himself the space to step away from work in his later years. But, just as it had done earlier in his life, lighting called him back. These days he balances his family-run lighting company with his new position as Project Executive at The Projects Group, a design and construction company that works on an array of projects, including museums, performing arts centers, and higher education facilities across the United States.

Now in his 60s, Walker is thinking a lot about legacy in his work. Through The Projects Group, he is able to work with museums and organizations, advocating for minority-contractors. In his own company, which has always been a joint venture with his wife, who he describes as its backbone, one of Walker’s daughter has been becoming a larger part of the business, and his other children are likely to follow suit. Beyond his own family, Walker is also teaching and training other young people in this work. Summers, from the GFAF, noted that Walker is a supportive leader to his team, offering his staff a combination of nurturing kindness while also providing autonomy.

Brian Dickson Jr., who has worked with Walker on a few projects, echoed the same sentiments, saying, “Learning a new skill can be intimidating, but Alfred made learning how to light art fun and worthwhile… his kindness, patience, attention to detail, and commitment to providing his clients with the utmost professionalism are admirable. Every workday felt like the warmth of a Sunday school class. Alfred made sure I was comfortable with every task and was quick to trust me to handle things on my own. He took me in and exposed me to a new side of the art world. Alfred’s success means a lot to me as a young Black artist. He is trailblazing for Black creatives, making room for us in spaces that usually exclude us.”

Walker recalled that even as recently as 2016, when the widow and daughter of Norman Lewis attended a reception for an exhibition of Lewis’ work at the Carter, they felt a sense of unease. Walker’s wife, Tina, stepped in, greeting them warmly, and spoke with them about the work her husband does. That small act of kindness was the beginning of a relationship between the Walkers and the Lewises. Later, Walker would go on to provide lighting services for the Lewis family’s private collection.

For his part, Walker recognizes how fortunate he has been in his career, and he concedes that there’s still a lot he wants to do: “Lighting art opened up a whole new world for me. I felt an excitement that I had never felt before. Even to this day, after 43 years, I’m still excited about what I do… my life revolves around art and I enjoy it. I do have a new generation that I want to train. There are a lot of people of color who have never been to a museum, but I think it’s worth something to develop a love for art. After I’m gone, I just want this to keep going. I want people to know we left a legacy.”

4 comments

Thanks for this well written article about Alfred Walker’s career and his contributions to the arts, paying his opportunities forward. Also, thanks for recognizing the mentoring Walker received from individuals at the Amon Carter Museum.

Mr. Walker has always been a focused and dedicated person. He continues to think outside the box, finding new solutions to old problems. His love for the preservation of art, is not a job for him, it’s a calling.

Thank you for such a worthy article on Alfred Walker. I worked with Alfred at the Amon Carter in the 1980s-90s and always admired his good nature and commitment to excellence. I am so happy to hear about the successful continuation of his career. Wishing you all the best in your retirement, Alfred!

Alfred is as skilled as they come. He artfully lit our original collection of photographs, paintings, and taxidermy with careful consideration. Your article reveals his journey in a thoughtful way – reflecting his thoughtfulness, kindness, and willingness to share his knowledge so that others may benefit. Thank you for highlighting such a well-deserved individual as Alfred. He is truly an artist in his own right.