The art dealer is often lost to history, cast into obscurity behind the artists they promoted. Take a few case studies: do you remember Paul Durand-Ruel over the reputable Claude Monet, or Andrew Bellamy over Donald Judd? While these are just two examples, the irony of this level of art world canonization is that the art dealer labors for the recognition of their artist while often sacrificing their own.

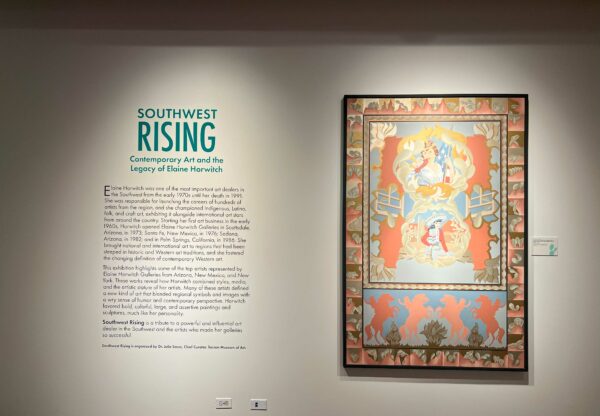

Artists whose work paved the way for New Western Art or Southwest Pop found their champion in Elaine Horwitch. On view at the Briscoe Western Art Museum in San Antonio, Southwest Rising: Contemporary Art and the Legacy of Elaine Horwitch immortalizes the formidable gallerist by epitomizing the strides she took to innovate Western art while familiarizing viewers with Horwitch and the artists she represented — notably, women and Indigenous artists.

“Southwest Rising: Contemporary Art and the Legacy of Elaine Horwitch,” on view at the Briscoe Western Art Museum in San Antonio. Photo: Caroline Frost.

The Briscoe’s installation of Southwest Rising is the latest iteration in a series of auxiliary exhibitions traveling nationwide. The debut show opened at the Tucson Museum of Art — which provided many of the 45 featured works — and is where Southwest Rising curator, Dr. Julie Sasse, serves as Chief Curator. Southwest Rising as an exhibition was born from Sasse’s book of the same title that functions partly as an art historical account of contemporary art in the American Southwest, partly as a biography of Horwitch, and part memoir of Sasse, who worked for Horwich for 14 years. Through both projects, Sasse pays homage to Horwitch as a pivotal figure for transforming the Southwestern contemporary art market, launching hundreds of artists’ careers, and throwing legendary parties.

Horwitch’s art empire began in the mid-1960s in Arizona, when she sold prints and lithographs from the back of her station wagon. Inspired by the sales model for Tupperware, Horwitch brought her product to people in their homes and various social gatherings; she called it The Art Wagon. In 1973, Horwitch opened her first eponymous brick-and-mortar gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona, called Elaine Horwitch Galleries. Over the next decade, Elaine Horwitch Galleries expanded to Santa Fe, New Mexico, Sedona, Arizona, and Palm Springs, California. Southwest Rising highlights some of the most popular artists with Elaine Horwitch Galleries and tracks the region’s growth in contemporary art and its stylistic expansion.

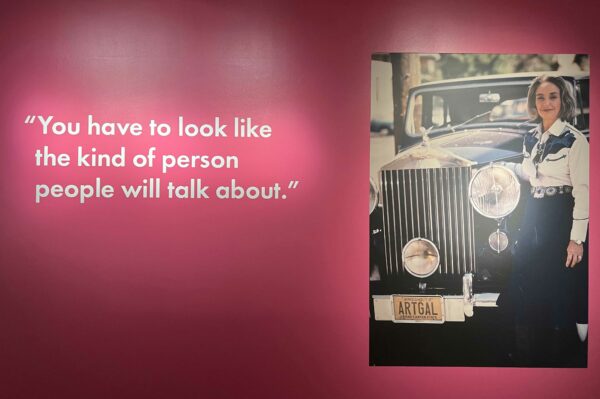

As I enter the exhibition space on the second floor of the Briscoe, located in downtown San Antonio, the introductory material describes Horwitch’s artistic preference for “bold, colorful, large, and assertive paintings and sculptures — much like her personality.” Southwest Rising effectively demonstrates both her distinct taste in art and her disarming demeanor. Hysterical quotes from Horwitch are interspersed throughout the exhibition, installed in vinyl on the walls. With each quote, Horwitch comes to life a bit more, like a friend in my ear doling out unsolicited advice, such as, “You signed up for this job. The more fame you get, the more people cut you down to make themselves to feel important, including me. That’s why I carry a gun.” She wasn’t being facetious either, she did in fact carry a loaded pearl-studded Smith & Wesson pistol.

Numerous portraits of Horwitch provide visual evidence of the kind of larger-than-life lady that she was. One photo shows Horwitch standing next to her Rolls Royce (with a vanity plate toting “ARTGAL,” of course), and another features Horwitch with her good friend (and collector) Robert Redford. But it wasn’t just Horwitch’s fabulous lifestyle and charisma that attracted artists. She worked hard to support them, and she was as socially progressive as she was commercially prolific.

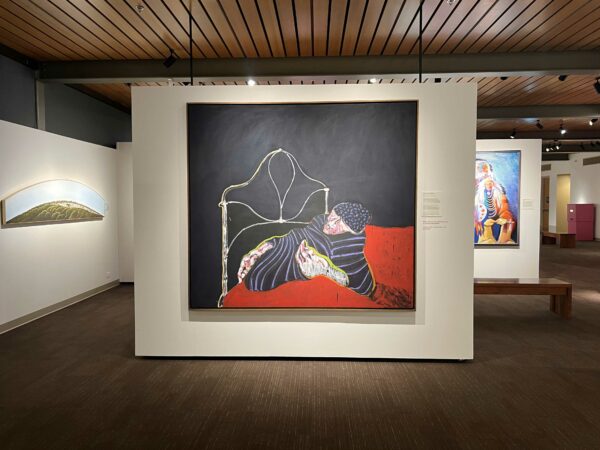

“Southwest Rising,” on view at the Briscoe Western Art Museum in San Antonio. Photo: Caroline Frost.

Veering left from the entrance, I arrive at the first grouping of artists: Women Artists. At the peak of Horwitch’s career, more than half of the artists on her roster were women, which is impressive considering across all four locations Elaine Horwitch Galleries represented over 200 artists. Horwitch is known to have regularly offered them monthly stipends and advance payments on sales, and she valued women whose work ushered in subversive feminist perspectives. Southwest Rising exhibits nine of Horwitch’s leading ladies, including Anne Coe, Susan Hertel, and Lynn Taber.

Taber’s featured painting, In Honor of the Potential Emancipation of the Prickly Pear and Katy Keene, America’s Pin-Up Queen (1976), exemplifies how the women of Elaine Horwitch Galleries used contemporary stylistic techniques to critique established social and political issues of mid-century America through the lens of the Western subject. Stylistically, Taber recalls qualities of Art Nouveau; sinuous curves in pastel blue, orange, gold, and green manifest organic forms, chiefly prickly pear cacti and red rock forms bordering the composition. Two rectangular registers are situated within the border, the bottom of which presents the motif of a Napoleonic equestrian silhouette, except this rider’s extended arm flails with thrill, rather than pointing decisively, and sports the curve of a cowboy hat rather than an imperial bicorne.

In the top register, the curvilinear design engulfs two female figures, separated into their own medallions. The woman on top is white, with fair skin and light brown hair that is held in place by a gold crown. A white wrinkled dress clings to her body as she lightly grasps the pole of an American flag in her left hand while catching the end of the flag in her right, draping its stars and stripes around her. She is delicately rendered, idealized, and too pristine to be real, like an allegory. The woman below her does exist, at least in popular culture, and would have been immediately recognizable in 1976 — she is Katy Keene, America’s Pin-Up Queen. With her signature jet-black hair and full red lips, she exists for all intents and purposes to adapt to any context or fantasy. Taber has rendered her fashioning a sombrero and a charro suit, straddling a wooden fence. Saguaro and prickly pear cacti frame her as the Southwestern landscape extends behind her.

Lynn Taber, “In Honor of the Potential Emancipation of the Prickly Pear and Katy Keene, America’s Pin-Up Queen,” on view in “Southwest Rising.” Photo: Caroline Frost.

The two women are portrayed in vastly different ways. One is painterly, and one is graphic, and their attributes are steeped in disparate symbolism. Yet, the compositional relationship between the two women draws a comparison: they are both objects of desire and are both exploited by this desire. The allegorical woman is manifest destiny personified, a colonizer’s pipe dream. Katy Keene is every woman and no woman at all, creating and fulfilling fantasies. Drawing from her experience as a woman, likely all too familiar with perpetual sexualization and objectification, Taber satirically mocks American colonialist perspectives of the Southwestern region, yearning for the emancipation of the land and its Native people from exploitation. This decolonial sentiment is echoed throughout the artists’ works who showed at Elaine Horwitch Galleries, especially the many Indigenous artists Horwitch represented.

Turning the corner into the next grouping of artists, Indigenous Artists, I’m stunned by Fritz Scholder’s Dying Warrior in South Dakota (1972). The simple composition and flat perspective do not lack formal expression. The bright red color field in the foreground burns against the charcoal black background. The figure, though clearly physically succumbing to their mortality, has disproportionately large hands and forearms, honoring their past as a warrior, as the title suggests. As a student at Sacramento City College, Scholder (Luiseño) studied under Pop Artist Wayne Thiebaud, whose work greatly influenced him stylistically. From 1964-1969, Scholder taught at the Institute of American Indian Affairs (IAIA) in Santa Fe, and, though he’d previously refused to paint Native American subject matter as a statement against the commodification of Native imagery by non-Natives, he is best known for his expressive paintings of Native figures.

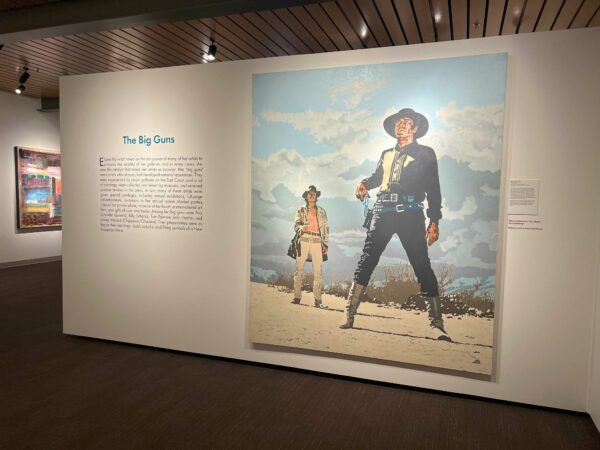

In Southwest Rising, the book, Sasse writes, “By depicting Native Americans on his own terms and in his own style, [Scholder] returned the subject of the Indian to Indigenous interpretations and forever shifted and expanded the notion of representation and identity.” After meeting Horwitch in 1972, Scholder became a household name at Elaine Horwitch Galleries, one of her “Big Guns,” as she called them, and he introduced her to his IAIA students Earl Biss (Apsáalooke/Crow) and Kevin Red Star (Apsáalooke), whom she took on as well.

Fritz Scholder, “Dying Warrior in South Dakota,” 1972, on view in “Southwest Rising.” Photo: Caroline Frost

In addition to many Indigenous artists, Horwitch also supported Latinx artists. Before exhibiting on the walls of Elaine Horwitch Galleries, Rudy M. Fernandez Jr. worked for Horwitch as a preparator. Featured in Southwest Rising, La Guadaplupana Cultural Icon (1997) is emblematic of Fernandez’s autobiographical practice. Drawing from his Mexican heritage and from living in New Mexico, his work often resembles retablos, featuring roses, knives, saguaros, and neon lighting. Fernandez taught at the Instituto Cultural Tenochtitlan in Mexico City and participated in many early Chicano exhibitions, such as Artistas de Aztlan in Seattle in 1975. In fact, Fernandez was the first Chicano artist on the roster at Elaine Horwitch Galleries, which he joined in 1981. Horwitch also exhibited the work of famed El Paso-born artist Luis Jiménez, whose work Jimenez at Adeliza’s Candystore is also on display in Southwest Rising.

Rudy Fernandez, “La Guadaplupana Cultural Icon,” 1997, on view in “Southwest Rising.” Photo: Caroline Frost

Though diverse in backgrounds and demographics, the artists Horwitch recruited found a throughline in their innovative approach to the genre of Western art, carving out their own niche: New Western Art. I slowly meander through the final groupings of artists in Southwest Rising, categorized by their adoption of the newest trends in contemporary art, such as abstraction, Pop art, and hyperrealism.

Indigenous artists James Havard (Chippewa/Choctaw) and Kay WalkingStick (Cherokee) used abstraction to interpret the region’s Native people and customs. On display in Southwest Rising, Havard’s New Mexico History Page 5 (1991) demonstrates his signature blending of fabrics and other found objects and materials with reproductions of Indigenous pottery and symbols. WalkingStick’s featured lithograph Cosmic Remnant (1998) is an expressive landscape scene, loosely abstracted by overlaid Indigenous symbols to explore the physical and spiritual significance of the land to First Nation groups. At a time when what is now referred to as Southwest Pop was not widely accepted in the world of Western art, Horwitch saw its potential and provided a seminal platform for the artists who created the style. A figurehead in originating Western Pop, Billy Schenck was one of Horwitch’s “Big Guns.” Inspired by the aesthetics of Spaghetti Western films, Schenck is renowned for painting photorealistic scenes of gunslinging cowboys and punk cowgirls, often paired with quippy text, in saturated tonalities. Schenck’s eye-catching painting Wyoming #44 (1973) in Southwest Rising epitomizes the movement with its pop cultural source material, large scale, and contemporary paint-by-numbers technique.

From left: Dick Jemison, “Detritus Series IV,” 2007; James Havard, “New Mexico History Page 5,” 1991; Kay WalkingStick, “Cosmic Remnant,” 1998; Joe Baker, “Bayed,” 1987, on view in “Southwest Rising.” Photo: Caroline Frost

As emerging Southwestern artists adopted new approaches to reflect their ever-changing physical, social, and media environments in the 70s and 80s, a gallerist with the hustle to promote their work was essential. Horwitch had the sway, swagger, and social network to connect artists to their clientele and to help forge a bustling creative community. She elevated underrepresented styles and artists, namely women, Indigenous, Latinx, craft, and folk artists, by exhibiting them alongside those who already held international acclaim.

Elaine Horwitch Galleries closed shortly after her death in 1991, but her legacy lives on through the artists featured in Southwest Rising and the eulogizing stories about her. Exiting the exhibition space, I spent a final moment with Elaine’s photo. It’s no wonder that she was referred to as the Annie Oakley of the contemporary art world. Sporting a denim prairie skirt, concho belt, boots, and a pearl snap, Horwitch reminds me, “You have to look like the kind of person people will talk about.” She, for one, still has people talking.

“Southwest Rising: Contemporary Art and the Legacy of Elaine Horwitch,” on view at the Briscoe Western Art Museum in San Antonio. Photo: Caroline Frost

Southwest Rising: Contemporary Art and the Legacy of Elaine Horwitch is on view at the Briscoe Western Art Museum through September 4, 2023.

Update August 14, 2023: This article has been updated to correct the name of an artist in the exhibition. The artist’s name is James Havard, not John Harvard.

1 comment

The artist James Havard was referred to in your article as John Harvard. The piece of art is his but his name is wrong. Please correct.