Para leer este artículo en español, por favor vaya aquí. To read this article in Spanish, please go here.

Although I am a monolingual English speaker, I am highly aware of language accessibility in art spaces, particularly in museums. The topic is important to me because just two generations back, both sides of my family were fully bilingual (Spanish/English), but through the common experiences of forced and self-determined assimilation, neither of my parents speak Spanish. I will add that, currently, there are ongoing discussions among non-Spanish-speaking Latinos about whether or not we should be caught up in the idea of speaking what is essentially a language forced upon our Indigenous ancestors by our colonizing ancestors. Even with this in mind, I often think about my parents and other second- and third-generation immigrants who struggle with walking the line of maintaining important cultural traditions while navigating the culture of Whiteness found in U.S. educational and professional spheres. Though cultural representation alone cannot change this larger issue, it is sometimes the first step or an open doorway to a sense of belonging in an otherwise unfamiliar space.

While working in North Texas museums, I was part of a small group of people advocating for the inclusion of Spanish language in wayfinding, promotional, and exhibition text, as well as in programming. For institutions that have historically defaulted to English-only text, this shift might seem overwhelming; not only does it mean double the printed text, but it also requires Spanish-fluent translators, editors, and visitor-serving staff, such as gallery guards and educators. While some North Texas museums, like the Dallas Museum of Art and, more recently, the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, have begun incorporating Spanish text into permanent collections and rotating exhibition design, most have not made much progress on this initiative. This is despite the fact that 37% of Dallas’ population and 26% of Fort Worth’s population speaks Spanish.

Through my travels this year for Glasstire, I was excited (though not surprised, due to proximity to the U.S./Mexico border) to see that museums in the Rio Grande Valley and in West Texas are regularly providing dual-language text for visitors. Though the International Museum of Art and Science (IMAS) in McAllen and the El Paso Museum of Art (EPMA) are smaller institutions, it is likely they have insights to share about the ins and outs of bilingual text in art spaces.

Established in 1967, IMAS has been offering both Spanish and English text in its exhibitions for a number of years, though its current staff could not recall when this practice went into place. For a city in which 72% of the population speaks Spanish, this is not surprising. Exhibition text at IMAS is primarily written in English and then translated into Spanish by Spanish-speaking staff members, some of whom act as translators, while others serve as editors. Even with a long history of undertaking this work, the challenges the museum faces regarding presenting bilingual text are similar to issues that any organization undertaking this work might experience.

A representative for IMAS explained, “One of the biggest challenges we face is variations in word use, colloquial terms, word preferences, and interpretation. We find that depending on who translates the text, certain terms may be translated differently. Even when we have vetted the text and shown it to multiple staffers or translators, we sometimes still receive feedback from visitors that we may not quite have the right terminology.”

As a Smithsonian affiliate, IMAS often has the opportunity to host traveling exhibitions from the national museum, through the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES) program. For the recent exhibition Life in One Cubic Foot, IMAS staff translated the English text provided by SITES into Spanish. Because IMAS provides text in both English and Spanish, it accepted the exhibition on the condition that it would contribute the translated text during the exhibition development stage.

Similarly, the El Paso Museum of Art (EPMA), which was founded in 1959, has been incorporating Spanish and English text in its exhibitions since it moved to its current location in 1998. Like IMAS, EPMA originally began offering Spanish text by having Spanish-speaking staff and interns complete the translations of prewritten English text. However, they often found that because Spanish differs regionally and from spoken to written form, it was necessary to work with a certified translator. So, beginning in 2017, the process was formalized.

Installation view, “Gene Flores: Chicano Proverbios and Dichos” at the El Paso Museum of Art, September 5 – November 7, 1999. Photograph courtesy of the museum.

At EPMA, exhibition text is written by the curatorial team, or for exhibitions traveling from other venues, like the recent show There Is a Woman in Every Color: Black Women in Art, which came from Bowdoin College, text is provided by the lending institution. The museum currently collaborates with the University of Texas at El Paso’s Translation and Interpretation Department and its director, Victoria A. García, who is also a member of the American Translators Association; they also work with the El Paso Interpreters and Translators Association. Claudia Preza, the Assistant Curator at EPMA explained that, “By working with local translators, EPMA ensures that the Spanish used is local, as opposed to other versions of Spanish used elsewhere.”

Elizabeth Catlett, “There is a Woman in Every Color,” 1975, color linoleum cut, screenprint, and woodcut. On view at the El Paso Museum of Art.

As a curator who organizes exhibitions, Preza says that one of the biggest challenges with incorporating Spanish and English text is planning for the display of double the amount of text which would otherwise be included. In addition to affecting the layout, this additional text can increase the show’s production time and the budget. However, the benefits outweigh the struggles. A 2022 study found that El Paso is the most bilingual city in the U.S., with 39% of its population being fully bilingual and 67% of its population speaking Spanish. And in addition to better serving El Paso residents, offering Spanish text also helps the museum accommodate its international audience: EPMA is located in the city’s Downtown Arts District, which is less than a mile from two of the three bridges that connect the city to Ciudad Juárez. While the museum does not gather information about where visitors are coming from, Preza noted that on average, about 900 people cross into El Paso a day.

Beyond exhibition text, EPMA also provides bilingual text on its website and in brochures available at the museum, like its map and family guide. Last year, the museum produced a video to share with tour groups in advance of their visit, and though it is voiced in English, it is available with either English or Spanish subtitles. Currently EPMA is working to translate other educational materials, like audio guides and augmented reality videos.

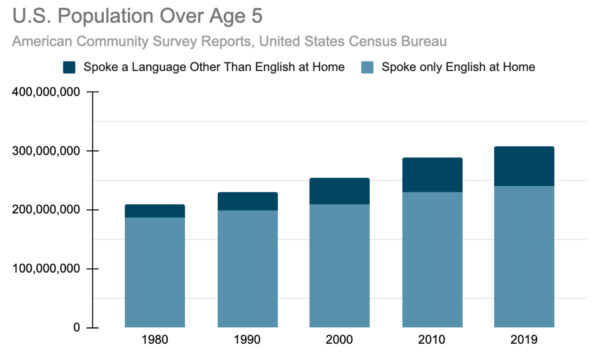

While estimates predict that by 2044 the majority of the U.S. population will identify as Black, Asian, Latino, Multiracial, or other non-white racial categories, the shift in language representation is discussed less often. The 2019 American Community Survey Report on Language Use in the United States illustrates an increase in the number of people who speak a language other than English at home. From 1980 to 2019, the number of people who speak a non-English language at home has grown by nearly 45 million. In this time, the overall percentage of this group of people has doubled, shifting from approximately 11 percent to nearly 22 percent of the U.S. population over the age of 5.

As the population of the U.S. grows and shifts, the need for information and programming presented in multiple languages becomes more striking. Texas museums and art venues looking to offer Spanish language text and programming can look to organizations closest to the U.S./Mexico border, in cities with larger Spanish-speaking populations, to learn key strategies related to language accessibility.

By offering information and programs only in English, museums are neglecting parts of their own communities that they are tasked with serving. And while it is true that art often transcends language, when exhibition text is only offered in English, it creates barriers to access important context for people who only speak, or are more comfortable speaking, a language other than English.